The first half of Swann's Way.

“…and with what an intensified melancholy, did I reflect on my lack of qualification for a literary career, and abandon all hope of ever becoming a famous author. The regrets that I felt for this, as I lingered behind to muse awhile on my own, made me suffer so acutely that, in order to banish them, my mind of its own accord, by a sort of inhibition in the face of pain, ceased entirely to think of verse-making, of fiction, of the poetic future on which my lack of talent precluded me from counting. Then, quite independently of all these literary preoccupations and in no way connected with them, suddenly a roof, a gleam of sunlight on a stone, the smell of a path would make me stop still, to enjoy the special pleasure that each of them gave me, and also because they appeared to be concealing, beyond what my eyes could see, something which they invited me to come and take but which despite all my efforts I never managed to discover. Since I felt that this something was to be found in them, I would stand there motionless, looking, breathing, endeavouring to penetrate with my mind beyond the thing seen or smelt…”

Hello. Happy 2025. This journal, initially supposed to be posted in early February, is a bit late. Everything seems very out of control right now and this is may be an attempt at control. 10 pages of Proust every morning and journalling a little bit every day until I have some semblance of understanding of the story feels like control.

My first journal entry—of what will eventually be 12—as I read all six volumes of the Modern Library edition of In Search of Lost Time, will consist primarily of first impressions. I will refrain from introducing any scholarship on Proust as I have spent the majority of January (and February) just trying to get a foothold. I think I have done that. I will be reporting on the first half of Swann’s Way now and the latter half in early March, continuing onwards, posting monthly, as I complete a volume every 2 months. You may notice the title of my publication, Time Regained, is a reference to the final volume—let’s hope I get there.

I want to share my own reading experience in order to cultivate less self-doubt in my formation of perceptions, opinions, and observations. This will be by no means a collection of argumentative essays, rather, it is a place to put my thoughts, constantly developing and changing as I work through Search. I have a feeling journal entry #12 will look very different from entry #1. Please feel free to comment and point out where I may be going astray, or where you feel I may be wrong and unenlightened (I am very okay with being wrong).

In terms of spoilers, there will be some. However, I’m not convinced that Search is a book that can be spoiled? It seems to me this is a story more about how we get there versus what actually entails at each beat of the story.

I will refrain from listing any unnecessary biographical information here as I would like to stick to purely the contents of the book, for now (Search is in and of itself very autobiographical, anyways). If you want to learn about more about Proust as a person and how he saw the world I would recommend How Proust Can Change Your Life by Alain De Botton. Due to the novel’s auto-biographical nature, I tend to use ‘the narrator’ and ‘Proust’ interchangeably when referring to the voice of the narrative.

For the first progress report, I want to stick to outlining some key themes I have picked up on in the 318 pages I have read thus far. There are so many brilliant fleeting quotable ideas that I could put in these posts and I suppose if you want to experience those you should read Proust for yourself; these journals are my attempt at finding thematic through-lines—mostly as a structure to hold on to when I begin to find myself getting lost. As previously mentioned, I will leave out any scholarly sources for now as I haven’t explored that world just yet, however, I will reference a couple paintings from Eric Karpeles Paintings in Proust as I think it is a wonderful companion to my reading.

There are an overwhelming amount of topics and themes in Search so I will limit this post to the ones that have struck me most thus far, one for each week of my reading. This first progress report may seem a bit of a summary or a very loose connecting of multiple sporadic dots. I hope my research will take some shape over the course of this year but please bare with me as I try to consolidate my thinking and seek what currently eludes me.

1. Anxious Attachment

The first half of Swann’s way is predominantly occupied by the first chapter, called ‘Combray,’ which primarily focuses on the narrators childhood. I was shocked by the current of anxiety that runs through Proust’s descriptions. Every situation is approached with an intense indecisiveness and sheer panic that I too experienced as a child. Proust’s parents refuse to acknowledge his apparent neuroticism in an attempt to help him overcome it, however, solace is only (momentarily) found after Proust has been relinquished of fault for his anxiety and granted an evenings sleepover with his mother:

“And thus for the first time my unhappiness was regarded no longer as a punishable offence but as an involuntary ailment which had been officially recognised, a nervous condition for which I was in no way responsible: I had the consolation of no longer having to mingle apprehensive scruples with the bitterness of my tears; I could weep henceforth without sin.” (pp. 50-51)

Describing this moment as a “puberty of sorrow, a manumission of tears,” Proust all at once realizes that, despite his sudden freedom from responsibility, he has affected the person he loves most (51). Proust is no longer passive in his existence. In this display of vulnerability and unexpected victory over his father, Proust feels that, despite believing he ought to be happy, he was not:

“It struck me that my mother had just made a first concession which must have been painful to her, that it was a first abdication on her part from the ideal she had formed for me, and that for the first time she who was so brave had to confess herself beaten. It struck me that if I had just won a victory it was over her…and that this evening opened a new era, would remain a black date in the calendar.” (p. 51)

Crying with his mother, Proust’s guilt establishes within him a first instant of consciousness, an understanding of his affect on others and, when witnessing his mothers age, he believes that he caused it: “I felt that I had with an impious and secret finger traced a first wrinkle upon her soul and brought out a first white hair on her head” (52).

All of this backstory is to say, I believe that Proust’s illustrious descriptiveness comes from an overwhelming sense of empathy and guilt. His anxiety causes an unrelenting questioning of past actions and his empathy allows for the capability to gaze into the mind of someone else and see themselves for who they truly are, from their intentions and desires to their innermost secrets. I have a feeling that Proust’s meditations in this early section provide the groundwork for our understanding of how his mind operates, how he percieves the world, and how he draws conlusions to make the various thesis statements he does throughout the book.

2. Accessing the Past Through our Senses; Accessing Each Other in Art

Speaking of thesis statements, how about that little french cookie. What has since come to be described as a ‘Proustian Moment,’ a sudden involuntary remembering of the past from a smell, taste, or texture, the narrator’s tasting of a madeleine brings him back in time to the summers he spent in his aunt’s house in Combray. This tasting of the madeleine and remembrance of his past seems to be a physical embodiment Proust’s goal with Search.

“But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop their essence, the vast structure of recollection.” (pp. 63-64)

If we are able to access memories through our senses, Proust also has something to say for recognizing each other in art. I believe this to be one of the stronger themes of the novel, or one I predict will continue across all six volumes.

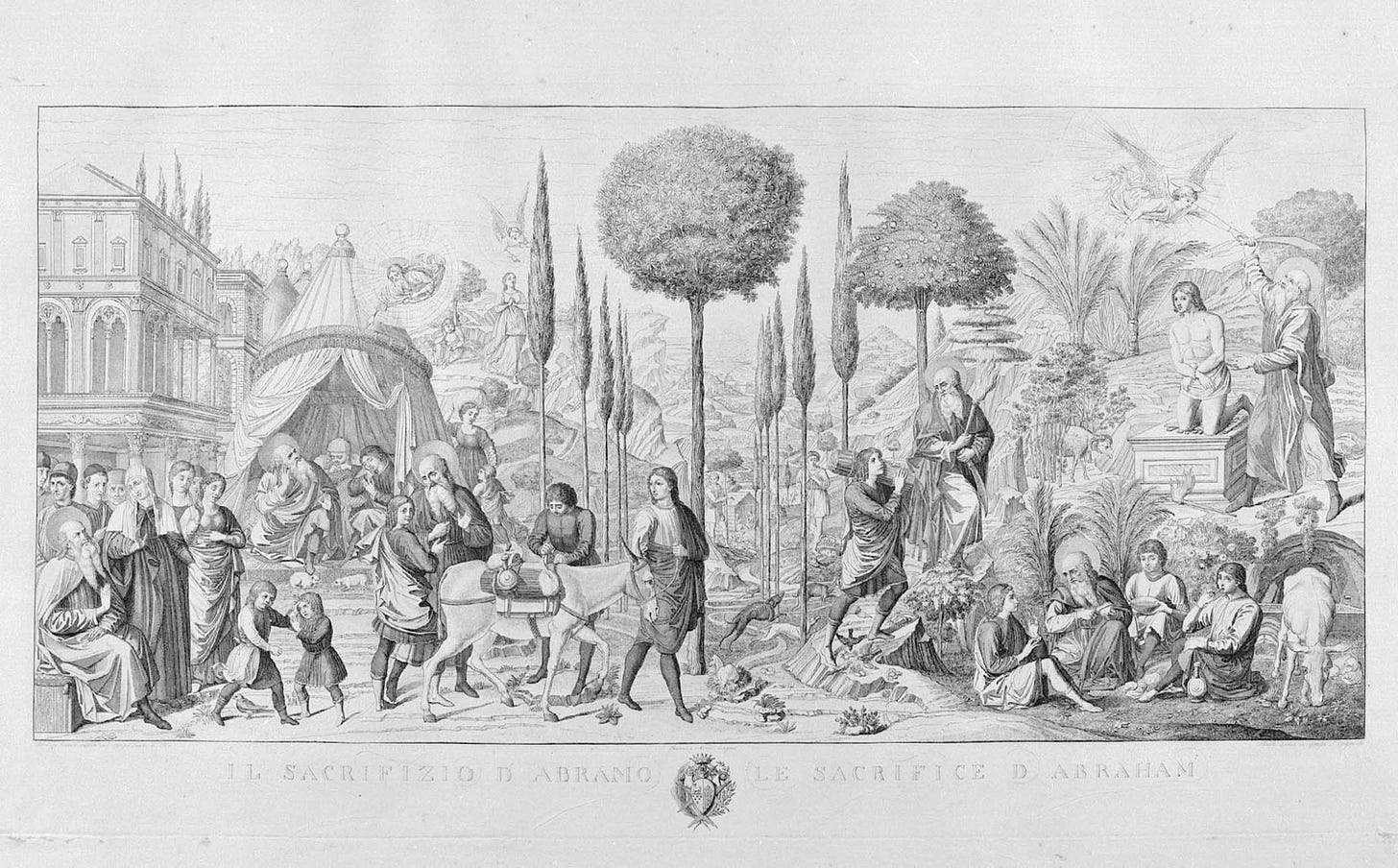

De Botton, in How Proust can Change your Life, argues that “the best indication of Proust’s views on how we should read lies in his approach to looking at paintings” (19). Whenever Proust looked at paintings he attempted to match the figures he saw in art with those he knew in real life. This is a habit he shares with Swann, a character in Search who, in the next part, ‘Swann in Love,’ expands the idea of seeing each other in art into seeing an entire society reflected back in those portraits (459). We will get there but not yet!

In noticing the relation between people we know and painted portraits, we can also extend that practice to portraits in fiction. Proust claims that the struggles of another person, observable only through our senses and “opaque” to us, occupy only a “small section of the complete idea” that, both ourselves and the person experiencing these struggles, are able to feel emotionally (116-117). Thus, it is the ingenuity of the novelist in their ability to transform these opaque sections of ourselves and others into immaterial versions presented in a story that “sets free within us all the joys and sorrows of the world” (117). The novel creates a place for us to sympathize with other humans and greater understand ourselves.

“It is the same in life; the heart changes, and it is our worst sorrow; but we know it only through reading, through our imagination: in reality its alteration, like that of certain natural phenomena, is so gradual that, even if we are able to distinguish, successively, each of its different states, we are still spared the actual sensation of change.” (p. 117)

The narrator will eventually go on to describe what he believes makes a good writer and explain why we often fail to recognize them during their time, but I will leave that for next month as it comes back around in part 2 of Swann’s Way.

3. Seeking Salvation; Seeking New Lives

If, then, we are able to access our memories from our senses and another’s soul in art, why is the narrator still so desperate to speak to an author named Bergotte and learn about the young girl who spends time with him? Proust has a tendency, reflected in his narrative and Swann’s actions later in the novel, to romanticize the access to another person’s mind. There is something so alluring about accessing someone else’s life; perhaps it is the nature of obsession that we place value on another’s knowledge and contents of their soul. Everything that is unknown haunts us and drives us to imagine what it is, in our intellect or experiences, that we may be missing out on.

The narrator realizes that, as he spends dinners conversing with his great aunt, the daughter of Swann, Mlle Swann, spends her evenings with Bergotte, hearing him speak “on all those subjects which he had not been able to take up in his writings” (138). This realization leaves Proust insecure in his own knowledge and thus his belief that the truth almost always lies in others begins to surface (Swann will also have these thoughts come up as a result of his jealousy for Odette). When speaking of Mlle. Swann, Proust claims:

“…nothing more remained but to know and to love her. The belief that a person has a share in an unknown life to which his or her love may win us admission is, of all the prerequisites of love, the one which it values most highly and which makes it set little store by all the rest.” (p. 139)

Does Proust have a true desire to know and love Mlle. Swann, or is it because she has access to knowledge, in her own experiences and in her connection to Bergotte, that, rather than develop romantic feelings for her, Proust wants to appease the feeling of how “coarse and ignorant” he may appear (138).

This novel is filled with back and forth anxious ruminations. Just 5 pages before feeling an overwhelming desire to access someone else’s life due to his own feelings of intellectual inferiority, the narrator has a revelation about finding his own opinions in the pages of Bergotte’s writing. I connected to this section with an alarming intensity. It is sort-of ironic how, in his desire to synthesize his views with those of the book he is reading, Proust is shocked to find himself and Bergotte sharing similar opinions, reaffirming him of his intelligence. I feel the same way when Proust makes an observation how I would or when, describing the various turnings of his anxious mind, I realized it turns the way mine does.

“But, alas, upon almost everything in the world his opinion was unknown to me. I had no doubt that it would differ entirely from my own, since his came down from an unknown sphere which I was striving to raise myself; convinced that my thoughts would have seemed pure foolishness to that perfected spirit, I had so completely obliterated them all that, if I happened to find in one of his books something which had already occurred to my own mind, my heart would swell as though some deity had, in his infinite bounty, restored it to me, had pronounced it to be beautiful and right…then it was suddenly revealed to me that my own humble experience and the realms of the true were less widely separated than I had supposed, that at certain points they actually coincided, and in my newfound confidence and joy I had wept upon his printed page as in the arms of a long lost father.” (pp. 132, 133)

I want to draw your attention to the fact that Proust assumes Bergotte to the role of being a “long lost father” (133). We know from earlier in the narrative that his paternal father isn’t the most gentle with him and Bergotte’s writing offers Proust a greater comfort and reassurance. At times, Proust harboured so many doubts in his abilities that he felt he was “wholly devoid of talent” and would desire to rely on his father to settle it for him. Intervention from his paternal father, however, would not ultimately suffice:

“But at other times, while my parents were growing impatient at seeing me loiter behind instead of following them, my present life, instead of seeming like an artificial creation of my father’s which he could modify as he chose, appeared, on the contrary, to be comprised in a larger reality which had not been created for my benefit, from whose judgements there was no appeal, within which I had no friend or ally, and beyond which no further possibilities lay concealed.” (pp. 244-245)

I want to ask whether these hopes of salvation by his father could also extend to Bergotte, saving him through the indirect validation of Proust’s intellect: “perhaps this lack of genius, this black cavity which gaped in my mind when I ransacked it for the theme of my future writings, was itself no more than an insubstantial illusion, and would vanish with the intervention of my father” (244-245).

You may notice this progress report is sandwiched between a quote. I chose it because I am drawn to Proust’s vulnerability in expressing his own shortcomings and failures. I split it to hopefully draw attention to the constant back and forth of his thinking: his moments of total confidence or seeming ineptitude followed by the salvation (or lack of) received by focusing on his senses. In the rest of the quote, at the end of this journal, Proust discusses the “illusion of fecundity” such perceptions bring him. There is a disparity here between the Proustian moment, our senses allowing us access into our memories, because, in a moment of doubt, Proust seems to be saying that there is still something beyond; that, at this moment in time, there seems to be something beyond the senses, beyond the material, that eludes the narrator’s grasp.

4. The Two Paths of Proust’s Memory and our Participation in their Walking

Despite this journal entry being obnoxiously long, I haven’t touched on the theme of memory nearly enough. Luckily, the first part of Swann’s Way leaves a lot to think about in that regard. The novel seems to orbit around two paths in Combray: the “Guermantes Way” and the “Méséglise” or “Swann’s Way” (188). These two paths have become parts of a routine, distinct signifiers to the different types of memory a walk on one versus the other would hold. For Proust in the current moment, however, these two paths shape both his memory and how he perceives his current reality.

“But it is preeminently as the deepest layer of my mental soil, as the firm ground on which I still stand, that I regard the Méséglise and the Guermantes ways. It is because I believed in things and in people while I walked along those paths that the things and the people they made known to me are the only ones that I still take seriously and that still bring me joy. Whether it is because the faith which creates has ceased to exist in me, or because reality takes shape in memory alone, the flowers that people show me nowadays for the first time never seem to me to be true flowers.” (pp. 259-260)

In one instance, Proust realizes that he only cared to see a person again because they reminded him of a hedge of hawthorns on one of these paths (261-262). From this passage, I’m interested in the idea that, for the narrator in this moment, he believes that “reality takes shape in memory alone” (260). Coming full circle—200 pages later—at the end of the first part, Proust describes a memory, or rather a collection of memories, which have been restored to him through the taste of tea (and the madeliene), of a love affair Swann had had before he was born. I wonder, how can the notion of reality taking shape in memory guide us through a reading of Swann and Odette?

“…It was certainly not impressions of this kind that could restore the hope I had lost of succeeding one day in becoming an author and poet, for each of them was associated with some material object devoid of intellectual value and suggesting no abstract truth. But at least they gave me an unreasoning pleasure, the illusion of a sort of fecundity, and thereby distracted me from the tedium, from the sense of my own impotence which I had felt whenever I had sought a philosophical theme for some great literary work.” (pp. 251-252)

— Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way